easyJet’s Amazon carbon offsets project is even more problematic than you thought

Indigenous peoples' rights are an issue too, not just methodologies

If you drive up and down the Inter-Oceanica Highway in the Madre de Dios region of the south-east Peruvian Amazon, just over the border from Brazil, it isn’t long before you hear about “los chinos.” That’s the somewhat crude shorthand for the Chinese-owned logging operations in the area, above all a 122,000 acre concession deeper into the forest and a sawmill in Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios’s biggest town.

That sawmill is run by one of the largest flooring manufacturers in China, Nature Home Holding Company, while the concession belongs to a firm known as MADERYJA for short, previously reported to be one of Nature’s “authorised manufacturers.” Certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and practising what they call “sustainable forest management”, 1000s of trees have been felled there over the years, including officially “vulnerable” mahogany and cedar as well as other valuable species like the particularly slow-growing shihuahuaco.

However, that’s not all the MADERYJA concession is. Bizarre or perhaps even ludicrous as it might seem, together with another FSC-certified and similarly huge concession adjacent to it run by a company known as MADERACRE, it doubles up as the “Madre de Dios Amazon REDD project” claiming to protect forest that would otherwise be knocked down and allowing other people to buy carbon “credits” to offset their emissions. No mention is made, it is worth emphasising, of the logging operations in the video promoting the project on the website of the Uruguayan company that developed it, Greenoxx, which simply states that the project area includes “unique and endangered rainforest species including the Amazonian mahogany and the cedar.” Who would guess, from watching that video, that some of those very same species, along with numerous others, have been chainsawed by Greenoxx’s project partners?

In May this year journalists from SourceMaterial, Greenpeace’s Unearthed team and The Guardian published articles about various major airlines claiming to offset their emissions by supporting projects like these, arriving at the significant - although unsurprising - conclusion that the companies’ “bold claims can’t be verified.” The Madre de Dios project, from which easyJet has been sourcing credits and thereby claiming “zero emissions” flying, was one of those featured by SourceMaterial and Unearthed. The journalists acknowledged that the project area is also two logging concessions and highlighted the fact that an absurdly inappropriate “reference region” - which includes the Inter-Oceanica Highway - had been chosen to measure the project’s success.

The reported response by Verra, a US-based not-for-profit organisation that has certified the project? Among other things, that the journalists “did not understand how its methodologies work” and their investigation was “fatally flawed.”

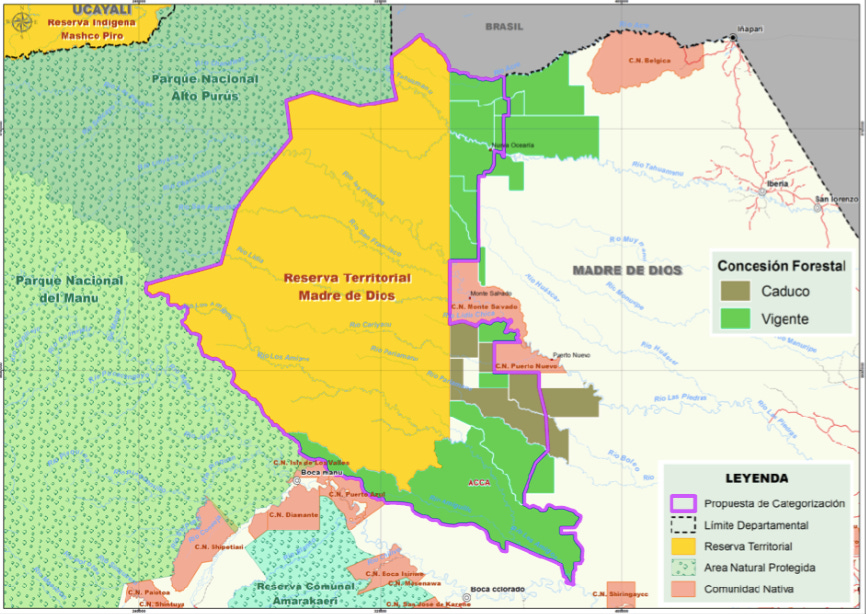

Equally as important as any of this, though, are the human rights concerns, which should render any disputes over methodologies irrelevant for a good chunk of the project. The “proposal to expand an Indigenous reserve bordering the project area” mentioned by SourceMaterial and Unearthed in their article is nothing new - and nor should it be considered somehow unreasonable or surprising. I say that because when the reserve was first proposed 20 years ago by regional indigenous federation FENAMAD, a large part of what became MADERYJA’s concession was included in it. However, when the reserve was actually established, in April 2002, it was much smaller than hoped - two million acres instead of six million - and then the very next month MADERYJA signed the contract for its concession. FENAMAD was so concerned about the potential impacts of logging on the indigenous people living in “isolation” whom the reserve was intended to protect that three years later they appealed to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which in 2007 ordered Peru’s government to “take all the necessary measures to guarantee [their] lives and integrity.”

Laura Posada, a Colombian lawyer from the US-based NGO Earthrights International which is supporting FENAMAD with its case at the Commission, emphasises that permitting loggers to operate in that area violates both Peruvian and international law.

“It’s incompatible with the isolated indigenous people living in the region,” she tells me, highlighting their right to self-determination and lack of immunity to outsiders’ diseases. “The concessions are a big threat to them.”

In a statement earlier this year FENAMAD said the initially proposed reserve’s boundaries had “corresponded to the area in which the existence of the peoples in isolation had been proven empirically”, and that they had been attempting to protect them from the “indiscriminate advance” of logging companies. “Our proposal was ignored and in 2002 the Madre de Dios Reserve was established - smaller than what we had requested and with arbitrary boundaries that left unprotected territories where people in isolation had been documented, and which ultimately were classified as Protected Natural Areas or Permanent Production Forests where extraction rights were granted to logging companies,” FENAMAD said. “That decision created risks for the lives and integrity of the Mashco Piro that persist to this day.”

To be clear, it isn’t just FENAMAD arguing that MADERYJA’s concession is part of the territories of indigenous people in “isolation”, or that their reserve should be expanded and the concession boundaries re-drawn. The same was also said in a 2016 report by researchers contracted by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), which in turn had been contracted by the Ministry of Culture (MINCU) as part of the administrative process to update the reserve in accordance with 2006-2007 laws. As well as listing evidence of the indigenous people in “isolation” that had been found in MADERYJA’s concession - “camp-sites, footprints, animals remains and poaching near the River Acre” - that report described the logging concessions in general as one of the biggest threats to them.

Later that same year, in November, the Peruvian state’s Cross-Sector Commission responsible for establishing reserves for indigenous people in “isolation” voted in favour of expanding the Madre de Dios Reserve as the MINCU-contracted report suggested. “The evidence [of them venturing beyond the reserve’s boundaries documented in that report] tallies with what the Ministry of Culture directly and others have been gathering,” stated the minutes of that Commission meeting.

Since then, things have become even more complicated because MINCU has been arguing that the reserve should be expanded to include part of MADERYJA’s concession but that the latter’s boundaries shouldn’t be redrawn and the company can continue operating - a proposal firmly rejected by FENAMAD as well as national Amazonian indigenous federations AIDESEP and CONAP, both based in Lima. Nevertheless, this remains clear: that MINCU has accepted that that area within the Chinese company’s concession forms part of the territories of indigenous people in “isolation.”

“It isn’t only FENAMAD saying this,” Daniel Rodriguez, a Spanish anthropologist who has worked for the federation for years, stresses to me. “The Peruvian state has also said that those are the lands of isolated peoples. These guys are saying: “Their territory is actually bigger than the reserve.””

In other words, not only does the “Madre de Dios Amazon REDD project” area double up as logging concessions, as pointed out by other journalists in May, but a considerable portion of it is within an area that for two decades the regional indigenous federation has been trying to include in an off-limits reserve and which for five years now the Peruvian state has also accepted is part of the territories of indigenous people in “isolation.” Worse, the latter are at serious risk from one of the project’s proponents, MADERYJA, which has not only entered their territories, chainsawed however many trees and even developed its own road network, but potentially exposes them, if some kind of contact occurred, to fatal epidemics. Even worse, another of the project proponents, MADERACRE, has publicly argued against expanding the reserve, as recorded in the minutes of a Cross-Sector Commission work-group meeting in February 2017.

When I mention to FENAMAD’s president, Shipibo man Julio Cusurichi, how the logging concessions double up as a carbon project, he describes it as “contradictory.” “They can’t know that in that area they’re violating the rights of these people, some of the last few living in isolation on the planet,” he says. “I think it’s important to publicise what’s going on there.”

Of course, this issue of the reserve makes the carbon project’s methodology even more problematic because it destroys the claim - fundamental to its raison d'etre - that without the project the area would be deforested. No other alternatives? Actually, as FENAMAD has been arguing, a good chunk of it could and should be part of the reserve for indigenous people in “isolation.” It is worth noting that, according to the US-based NGO Amazon Conservation Association, the rates of deforestation in such reserves in Peru, now numbering seven, are lower on average than even in the country’s “protected areas”, which include national parks.

Does easyJet really want to continue sourcing carbon credits from a project like this? Apart from the obvious fact that no one is cutting down more mahogany, cedar and shihuahuaco etc in that part of the Amazon than two of the project’s proponents, not to mention the equally obvious problems with the methodology, the lives and futures of some of the most vulnerable, most remote-dwelling indigenous people in the world are potentially at stake. easyJet replied to my question claiming it “employs a rigorous process to select the carbon offsetting projects” it works with, and all that “meet the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Gold Standard or Verified Carbon Standard certifications.”

“The Madre de Dios project meets these standards and continues to be rigorously audited by Verra on criteria including the safeguarding of the rights of indigenous communities and it has continually met these standards since it was launched,” easyJet tells me. “The robust standards in place alongside the expert advice and due diligence we receive continue to inform our confidence to support this project. Nonetheless, if we became aware that these standards were not being met, we wouldn’t hesitate to review our project participation.”

When I asked Verra about the reserve, they ignored my questions and gave the impression of not understanding the issue at all. “Decisions about the boundaries of territorial reserves are a matter for the government in question,” a spokesperson tells me. “At present, the boundaries of the territorial reserve and the project area do not overlap and have never overlapped.”

Greenoxx declined to comment.