Most impacted by Bolivia’s worst ever fires? Indigenous land and protected areas

NGO report concludes over 12.5 million hectares of South American country burned last year

In early October last year, while making a film for the UK-based Gecko Project, four of us visited an indigenous territory, Lomerío, in the Santa Cruz region in eastern Bolivia. One of the things we heard from community leaders there was that although, over recent decades, they have managed to preserve much of the forest in their own territory, they were still being severely impacted by the clear-cutting and fires that have been going on, year after year, in the areas surrounding them.

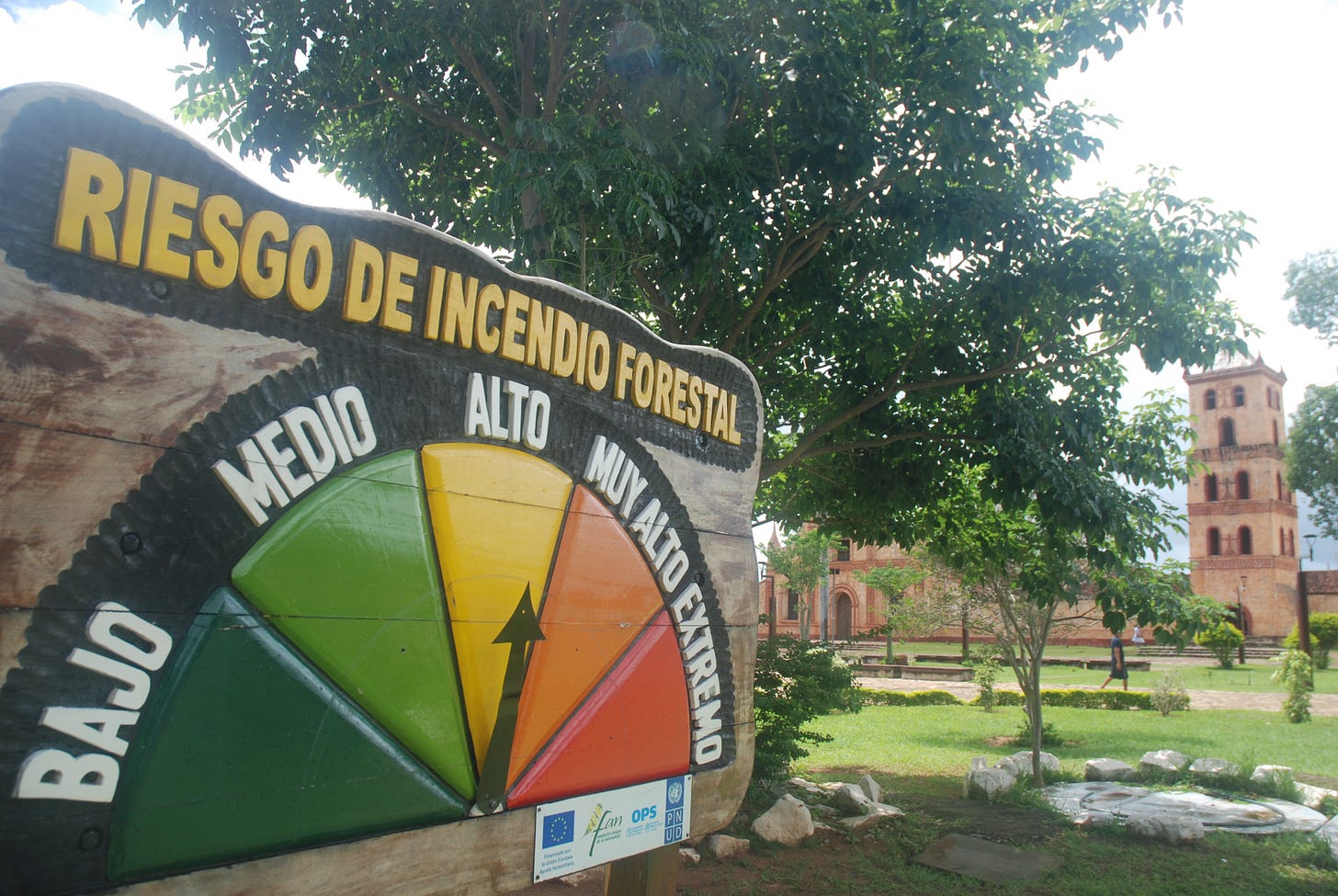

2024 turned out to be the very worst ever year for fires in Bolivia’s history: more than 12.5 million hectares of the country burned, according to a recent report by the Bolivian NGO TIERRA, and September and October, precisely when we were there, were two of the three hardest-hit months of all. In Lomerío the smoke in the air was palpable - you could see it, smell it, feel it.

“You can see how the environment is polluted here, but that’s not because of what’s happening in our territory,” says Maria Choré, president of Lomerío’s women’s federation, towards the end of The Gecko Project’s film, Bolivia Burning, which has been shown at various venues in Bolivia and is now pending a wider, international release. “For example, last week, a fire blew in, but it came from a property belonging to an “intercultural” community that borders our territory, as well as other properties around us.”

Other indigenous territories and communities were absolutely devastated by the fires. In fact, according to TIERRA’s report, 30% of the areas that burnt across Santa Cruz fell within indigenous territories, while 27% was in protected areas, and 13% on other land belonging to the state.

In other words, the 2024 fires in Santa Cruz - where in total 8.5 million hectares burned, making it easily the worst-hit region in the country - appear to have impacted indigenous people more seriously than anyone else.

In a sense, the most affected indigenous territory of all was Monte Verde, which the Lomerío leaders whom we spoke to mentioned numerous times. Almost 40% - 838,452 hectares - of their land was burnt, according to TIERRA. The only indigenous territory that had a larger area affected was Guarayos, a 6.5 million hectare area, where almost 1 million hectares - roughly 15% - were burned.

However, as TIERRA states in its report, the fact that the fires affected so much indigenous land doesn’t mean that indigenous people themselves were directly responsible for them. Other factors were at play too: fires coming in from surrounding areas, as Maria Choré told us happened in Lomerío, or other people starting them. The latter include “soy farmers and cattle ranchers” who “take advantage of the grey area existing between the powers of the Bolivian state and the self-determination of indigenous peoples” to “sign agreements with indigenous territories to take over their forests and clear them illegally”, and illegal settlers who just turn up and haven’t signed any such agreements.

What are the underlying causes of the fires in Bolivia, which last year lost more tropical forest than any other country in the world except Brazil? TIERRA’s report points the finger at the usual suspects: legislation, regulations, government policies and state agencies promoting or facilitating the “accelerating and uncontrolled” expansion of the agricultural frontier, together with “irresponsible fire management”, lack of enforcement, land trafficking, political patronage, and ongoing global demand for soy, soy-derived products and beef.

One of the findings that comes through most strongly in TIERRA’s report is that, contrary to how certain mainstream media reported it, the fires last year were not “isolated natural phenomena” - or “wild”, to put it another way - but the direct result of people clearing the forest to make way for large-scale agriculture.

“It’s imperative that every Bolivian understands,” writes TIERRA’s director Juan Pablo Chumacero Ruiz in the report’s foreword, “that the forest fires in Bolivia are the result of an unsustainable agricultural development model that is prioritising the expansion of monoculture crops over fundamental ecosystems.”

For a trailer of The Gecko Project’s film Bolivia Burning, see here. For more information, see their website. For updates, follow The Gecko Project on Instagram and X.